La Cosa NAFTA

February 3, 2020

This blog was originally posted on Quill Intelligence in March, 2019.

Why go with the Ancient when you can go Mod and have it both ways? There still exists a place, or two, where Greek meets Latin, where you don’t have to choose which of the cultures bests the other, because you can indulge in both at the same time. The journey requires you venture to the tip and heel of Italy’s boot, to the regions of Bovesia and Grecìa Salentina. There, Griko is spoken as it was when the Greeks first crossed the Strait of Otranto in the 11th century BC, where the transcendental turquoise waters of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas meet as one. In that Griko and Standard Modern Greek are close cousins, you can partake of the delights of both Italy and Greece without moving an inch.

For a time, Italian authorities dismissed the Calabrian region as a backwards farming province where olives were pressed, and lemon juice flowed from some of the world’s most pristine or- chards. But it seems the Greeks imported more than their agrarian acumen. From the Greek andrangheteia, meaning a “society of men of honor and valor,” the ‘Ndrangheta was born. Pro- nounced un-drung-get-a, it is the Calabria-based mafia you’ve never heard of. Prosecutors have characterized the ‘Ndranghetaas as the most powerful organized crime syndicate in existence. Its network includes 120 countries and income estimated to have crested $60 billion in 2014. This or- ganization’s scale easily surpasses that of Italy’s second-largest La Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian mafia whose infamy is immortalized in Mario Puzo’s brilliantly-crafted Godfather.

The 1950s marked a critical time for the Siderno branch of the ‘Ndrangheta as key members mi- grated to Australia and Canada. Michele “Mike” Racco, who settled in Toronto in 1952, went on to rise to the top ranks of the international organization. By 2010, after forging ties with Columbia’s drug cartels, investigators characterized Toronto’s ’Ndranghetabranch as having climbed “to the top of the criminal world” with “an unbreakable umbilical cord to Calabria.” Though exact figures are elusive, the closest parallel to ’Ndrangheta is the Sinaloa Cartel founded by Joaquín Archival- do Guzmán Loera, or not so affectionately known to his victims as “El Chapo.” Experts on cartels suggest that despite his incarceration, the Sinaloa Cartel rakes in over half of Mexico’s estimated

$40 billion in annual illicit profits from its dealings with the U.S. With an obscene total of $150 billion in profits per annum tied to the drug trade in the United States,the Canadian arm of ‘Ndrangheta, the Sinaloa Cartel and other rivals will never cease to wage war for their fair share of a divided continent.

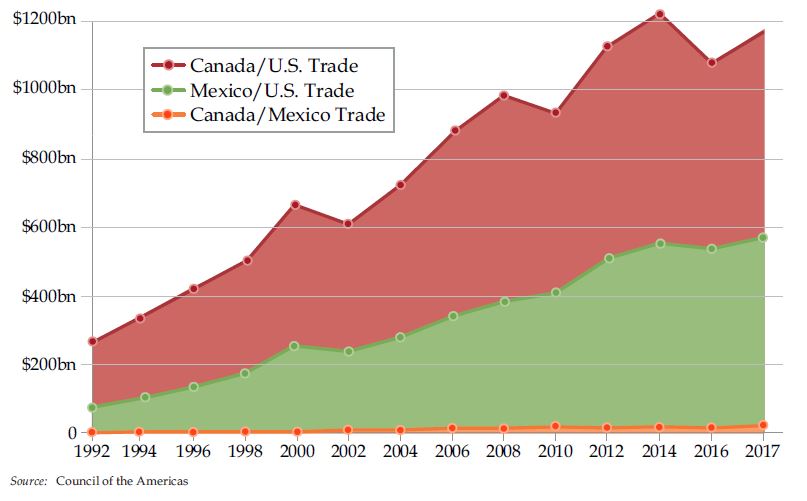

Seeking not to carve up, but to unite the continent, is NAFTA. An estimated $1.3 trillion in trade took place between the U.S., Canada and Mexico in 2018. Since NAFTA went into effect in 1993, total trilateral trade has exploded by more than 400%, placing into context how high the stakes are for our two NAFTA partners who are sure to be closely monitoring trade negotiations between China and the United States. It is hoped that in the end, there will be more winners than losers, but it is equally naïve to presume no collateral damage to other countries once the ink dries.

Shall We Make a Trade Deal?

Speaking of dried ink, the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) has yet to be ratified by the three countries. One criticism of the new deal centers on limitations on investors-state dispute settlement (ISDS). Arbitrations are conducted within an entity housed inside the World Bank and to date the 16 cases filed against the U.S. by foreign firms have ruled in favor of the

U.S. Under USMCA, U.S.-Canadian investment disputes will have to be resolved in Canadian or U.S. courts or through state-to-state diplomatic proceedings, cumbersome and potentially biased avenues. Mexico and the U.S. agreed to keep ISDS but only as it pertains to energy, power trans- mission, telecommunications, transportation and infrastructure projects.

Proponents of the deal funded by Canadian interests and U.S. companies that would benefit from expeditious ratification have gone so far as to launch a TV ad campaign urging Congress to act. Democrats, who now control the House, say the USMCA lacks labor and environmental enforce- ment measures while some take issue with intellectual property protections that they say could freeze already-high prescription drug prices.

Separately, Canada and Mexico have both indicated steel and aluminum tariffs imposed by the Trump administration in the name of national security be lifted. In exchange, the two countries will remove retaliatory tariffs they imposed, mostly on American agricultural exports. Trump has indicated that lifting the tariffs will coincide with the imposition of fresh quotas.

As if things weren’t complicated enough, Mexico’s Congress is under the gun to pass a labor-re- form package by the end of April that both Canada and the U.S. consider to be a deal-breaker. The lifting of steel and aluminum tariffs would, of course, need to come first according to Mexico’s representatives.

In recent testimony to the Senate Finance Committee, a contingent of Republicans urged U.S. trade representative Robert Lighthizer to resolve the tariff issue to which he responded, “I think there’s a sweet spot there that allows us to have a solution that satisfies Canada and Mexico and also maintains the basic integrity of the program.”

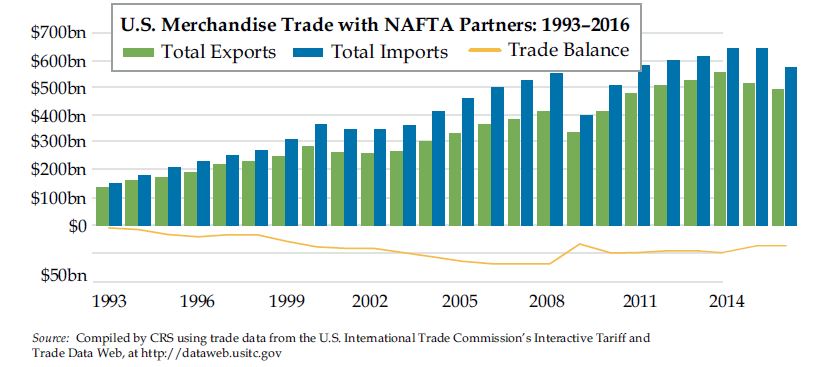

There is no putting the genie back in her bottle. As contentious as negotiations might be after the shift in Congressional leadership, reversing course with our two closest trading partners would be hugely disruptive to the economies of all three parties involved. Since 1993, the growth in trade with NAFTA partners has outpaced that of non-NAFTA countries, first surpassing the $1 trillion mark in 2011. By 2016, Canada was the leading market for U.S. exports, while Mexico ranked second with the two accounting for 34% of total U.S. exports. On the import side, after China, Canada and Mex- ico ranked second and third, respectively as suppliers of U.S. imports commanding a 26% share.

Post-NAFTA Growth on Both Sides of Trade Ledger Robust

Of the two trading partners, however, it is Mexico that has benefitted to the greatest extent. Economic integration between Canada and the U.S. was well underway when the original trade deal went into effect. Backing out, an acceleration in economic growth on a global scale further accelerated the growth of trade with Mexico and the U.S.

Though the spectrum of goods traded is wide, crude oil and petroleum products are a crit- ical component. In certain years, excluding them produces lower trade deficits, and in some cases, surpluses. In the decade to 2016, petroleum products have accounted for 10-17% of total trade with NAFTA partners.

As with other industries, it’s a tale of two trading partners when it comes to petroleum. Ravaged by a lack of investment, the depletion of its most prolific fields and precious few new finds, Mexico’s state-owned oil giant, Pemex, produced just 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd) in January, a record low in data back to 1990 and less than half its 2004 record 3.4 bpd production level. So negligible is petroleum trade with the U.S., once U.S. petroleum imports to Mexico are taken into account, Mexico’s net exports to the U.S. turn negative.

Mexico’s new leftist President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, who took office in December has committed to growing Pemex’s output to around 2.5 million bpd by the end of his six-year term in 2024. His cancelling of oil and gas auctions to private and foreign oil companies leaves the onus on the country to foot the bill to rescue the once great oil firm.

Doubts about the debt-laden country’s wherewithal prompted ratings agency Standard & Poor’s (S&P) to slash not only Pemex’s credit rating but to cut to negative from stable that of Mexico’s government and a range of major Mexican financial institutions and companies. S&P also lowered its outlook for 77 financial institutions. Of Pemex’s fragile finances, S&P cautioned that, “The government’s financial support, in order to restore credit fundamentals, falls well short of the company’s multi-annual capital investment needs.”

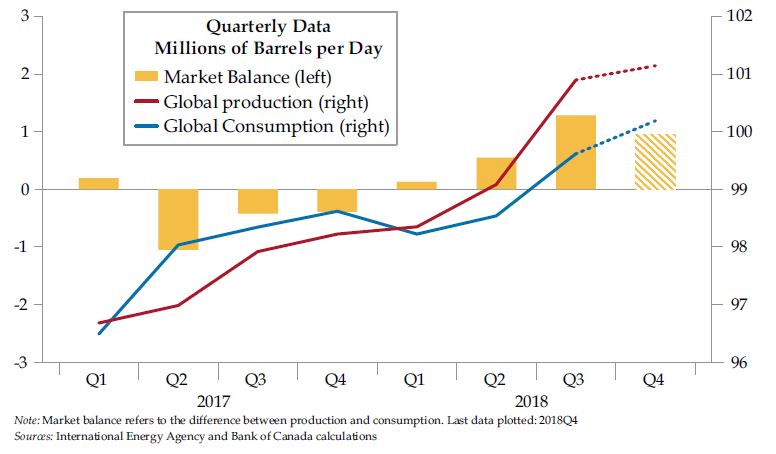

The story is a happier one for Canada, a net exporter which sent 2.8 million bpd to the U.S. in 2018, up 43% from 2014 and 250% from 1.4 bpd in 2002. That is not to say the shale revolution in the U.S. and rising global oil production in general have been all good north of the border. By the last three months of 2018, global oil output was about 3 million bpd higher than the same period in 2017. About two-thirds of that was attributable to higher U.S. production.

Global Production: The Shale Revolution in Pictures

The Bank of Canada’s (BoC) January Monetary Policy Report noted that the 25% decrease in aver- age oil prices since its October report was partially a reflection of steadily rising U.S. production and increased output from OPEC countries as well as trade and geopolitical concerns that were dampening global demand. As the BoC noted, looking ahead, “There is considerable uncertainty around the future path for global oil prices. The most important considerations are whether supply continues to outpace demand and whether market concerns about the US–China conflict abate.”

Landlocked Alberta’s overreliance on the U.S. as the sole buyer of its crude and the inability to build pipelines has further constrained Canada’s ability to capitalize on rising overseas demand. Looking ahead into 2019, the excess supply drag on Canada’s economy looks to persist. Over the longer term, the rise of U.S. shale production should make Canada’s economy more sensitive to the vagaries of U.S. business cycles, which we’ll touch on shortly.

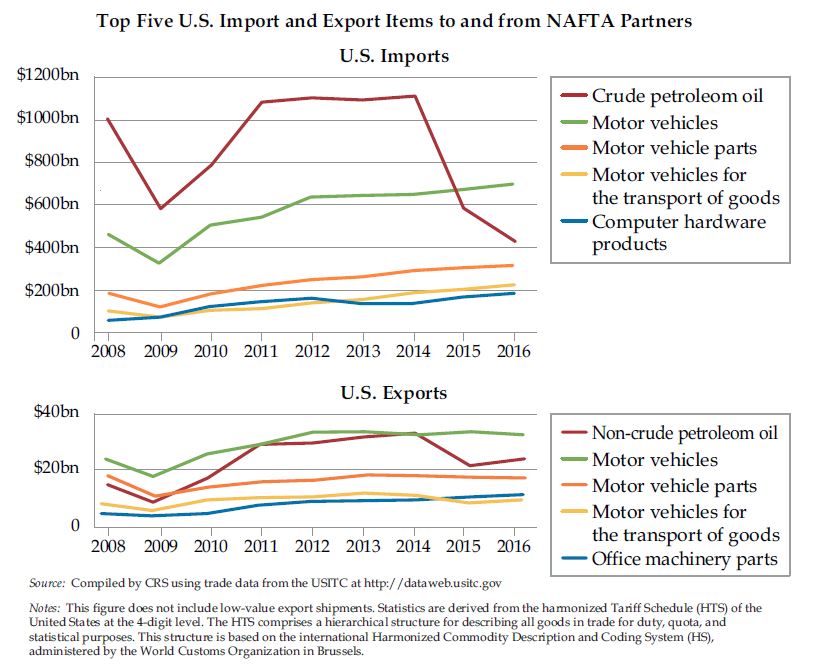

Suffice it to say, NAFTA encompasses much more than petroleum products. In fact, crude oil was the second-ranked U.S. import in 2016 after motor vehicles. Crude was followed by motor vehicle parts, motor vehicles for the transport of goods and computer hardware.

The flip side is what the U.S. exports to its NAFTA partners, which largely resembles what it im- ports, which is no accident – that’s why they’re called supply chains. Once again, for 2016, the top five U.S. exports were motor vehicle parts, non-crude petroleum oil products (mainly gasoline), motor vehicles, office machinery parts, and motor vehicles for the transport of goods.

We Bring it in & Ship it Back Out

Thriving activity at borders necessitates that some states have benefitted more than others in a post-NAFTA world. That said, Canada and Mexico hold both of the top two export destination spots for 25 U.S. states, including eight of the 10 biggest state economies. While Mexico tends to be in that #2 spot, it’s by and far the #1 destination for the nation’s biggest exporting states, Cali- fornia and Texas. In 2017 alone, Mexico traded $260 billion with the Golden and Lone Star states.

If anything, the growth has accelerated in recent years. Trilateral trade among NAFTA coun- tries rose by 6.5% in 2017, Trump’s first year in office, amidst rally cries to withdraw from the deal altogether from trade hawks such as Peter Navarro who was brought on to advise Trump in April 2017. California and Texas didn’t blink, with each increasing their exports to Mexico by 6% in 2017 despite the beating of the drums. Mexico buys a stunning 37% of Texas’ exports and 17% of those of California.

An aside, the continued focus on China is not without merit given evidence its firms are in the habit of stealing intellectual property from ours. In 2017, the U.S. trade deficit with China was $375 billion, more than five times the $71 billion deficit it ran with Mexico and more than 20 times its $18 billion deficit with Canada.

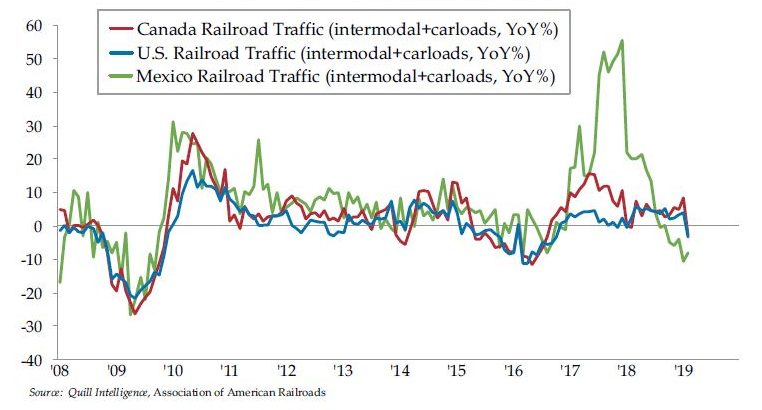

As vexing as the challenges are with China, it’s apparent that all three countries depend on its growing market. Gasoline-powered car sales in China peaked in 2017 – think gas-guzzling GM SUVs. It’s no coincidence that as Chinese car sales began to falter last year, intermodal rail traffic between Mexico and the U.S. collapsed. In January, car sales in China slipped 16% over the prior year, tacking on a seventh consecutive month to a string of year-on-year declines.

Shall We Manufacture a Car?

If you look at Canada relative to the U.S. in isolation, you see that while the spike in trade and subsequent collapse were not near as dramatic, the declines have nevertheless been steady and have now returned to negative territory. Two opposing forces were at work. U.S. shale production picked up as oil prices lifted off the floor, diminishing demand for Canada’s heavier crude imports. At the same time, residential real estate in the U.S. began its slow descent leaving it 9.2% below its April 2018 high this past January.

What the future holds will depend in part on whether China’s stimulus manages to reverse its economy’s slowdown. Some estimates suggest China printed the equivalent of 5% of its GDP in January alone to jump start its economy. Even taking China’s waning demand for cars out of the picture, based purely on U.S. domestic demand, it would appear car production is poised to be cut throughout North America, taking more of Mexico’s production capacity offline.

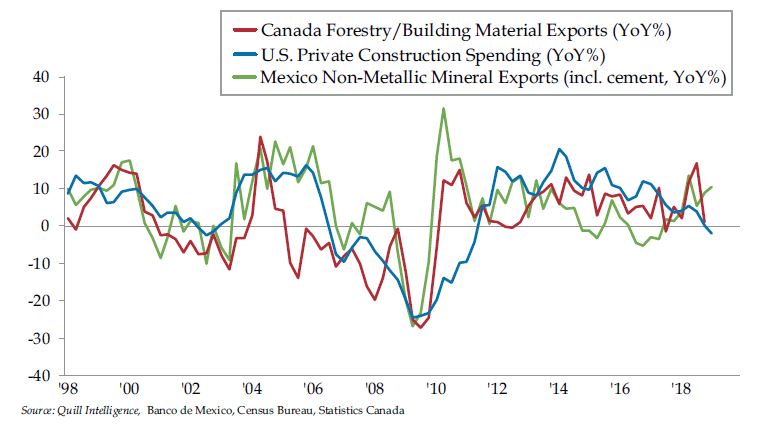

As for construction, the near-term prospects for Mexico’s other industrial behemoth, Cemex, could come down to the monies states and the federal government are plunking into infrastructure repairs in the U.S. In January, public spending on construction spiked 4.9%, the biggest increase in 15 years. As for the other uses for cement and Canadian lumber, this next graph suggests the best of times may have come and gone. Bear in mind, most baby boomer homeowners still reside in their homes. As that mega-tide begins to turn, it will become a secular drag on new home construction as millennials struggle to absorb the existing supplies making their way to market.

Mexico Hoping for Halcyon Days for Bridge, Road & Tunnel Repair Canada Pondering the Future Demographic Drag on New Home Construction

In a way, Canada’s fortunes have been similarly tethered to those of China, albeit in more subtle fashion. As has been bandied about, guesstimates as to the magnitude of Chinese foreign flows fleeing its shores venture into the trillions. You’ll not be accused of hyperbole in Toronto or Van- couver given the acute unaffordability of housing in these two cities that reside on the top 10 list of the world’s most expensive markets.

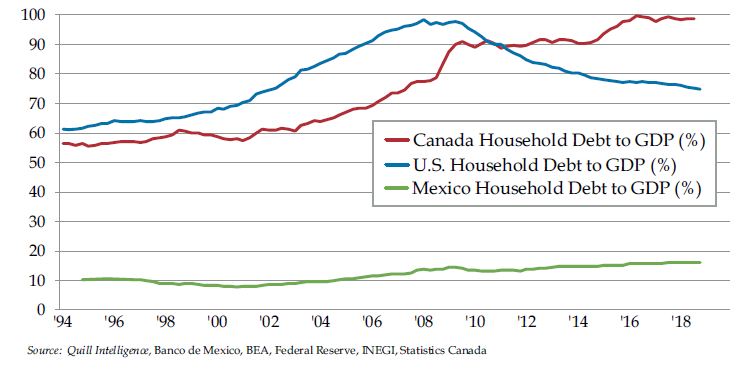

Look no further than Canada’s household debt-to-GDP ratio to appreciate how far households have had to stretch to afford housing in recent years. Even at the heights of the housing bubble in the United States, household debt-to-GDP did not touch 100% as it has recently in Canada. As for Mexican households, growing its middle class via burgeoning mortgage and consumer debt markets has been a long slog. At 16% of GDP, household debt has roughly doubled off its 2001 lows. Recent reports, however, indicate political uncertainty has quashed both the supply of and demand for household credit.

What a Difference Several Borders Make in Household Access to Debt

Though most on the sell-side remain in denial mode, we’ve begun to wonder which of the three countries will beat the other two into recession. If past is precedent, Canada will be the laggard in the best of ways.

The Economic Cycle Research Institute’s (ECRI) Lakshman Achuthan has long studied the three economies and their economic interdependence. As he explains,

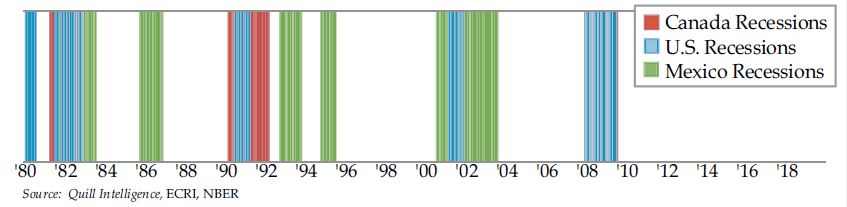

“In the postwar period Canada has had only five recessions; there were U.S. recessions associated with each of those. But the U.S. has had 11 recessions in that period, six of which Canada dodged. So, Canada is much less sensitive to the U.S. business cycle than even most Canadians realize. Mexico is a bit different. Since the earlier 1980s it’s not only gone into recession every time the U.S. has, but also it went into recession during the mid-1980s and mid-1990s U.S. soft landings.”

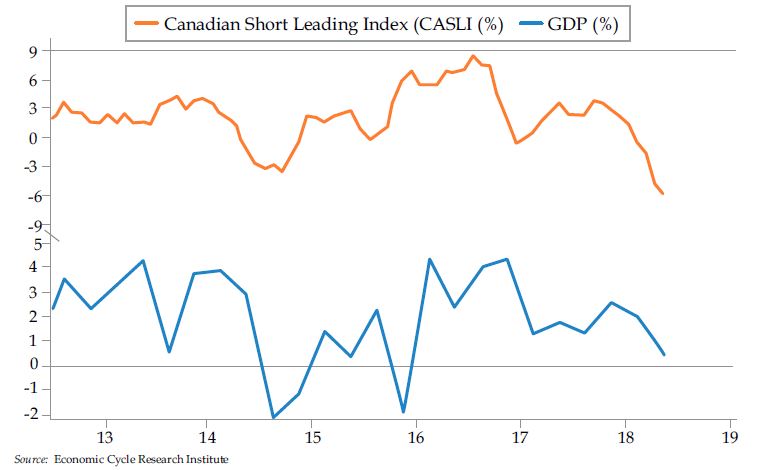

Achuthan first noticed the slowing in Canada’s economies in mid-2018 given its proprietary Cana- dian Short Leading Index, which leads GDP growth by about a quarter, had rolled over. Clearly the Bank of Canada (BoC) did not receive the same memo as it was as hawkish as the Federal Reserve headed into this year. In January, the BoC asserted that, “the policy interest rate will need to rise over time.” And then, in a Powell-esque blink of an eye, the BoC pivoted.

Will Canada Be the First to Succumb to Recession?

Achuthan added that, “Though the central bank hopes the global slowdown is temporary and would be ‘buoyed by the resolution of trade conflicts,’ its latest minutes were more reticent about domestic personal consumption growth, which has actually fallen to its lowest reading in nearly six years.” A pivot indeed.

In that the U.S. has never escaped recession when Canada succumbs, and given Mexico is always in contraction with the U.S., it would seem to be just a matter of time before we will be adding another candy stripe to the next chart that is dominated by the green of Mexico’s flag. Any way you look at it though, we can all agree that the longest stretch of easy monetary policy in the history of the world has managed to buy a remarkably long stretch of economic prosperity across the continent.

Time to Dust Off the Recession Crayons

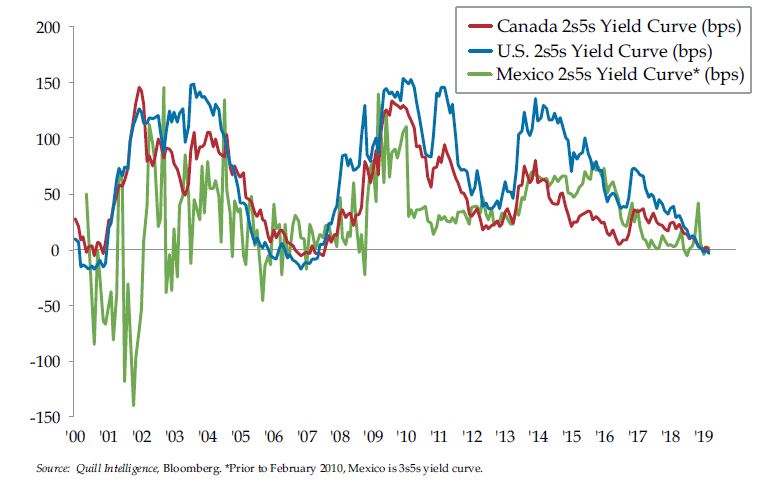

Any economist worth their salt would ask to compare and contrast the countries’ yield curves. The concept of inversion, after all, knows no language barriers. It is never a normal state of affairs if long rates are yielding less than those of shorter maturities. All inversions precurse recession. Knowing as we do that 5-year yields fell below those of 2-year yields in December in the U.S., we decided to stack the same two maturities against one another in Canada and Mexico to look for any parallels. While Mexico’s curve moves around like the jumping beans of its namesake, the difference between its and Canada’s 2-year and 5-year bonds did invert right alongside that of the United States. So we can safely check that off our list.

In a Bumpy Ride Down, the NAFTA Curve Inverts in Sync

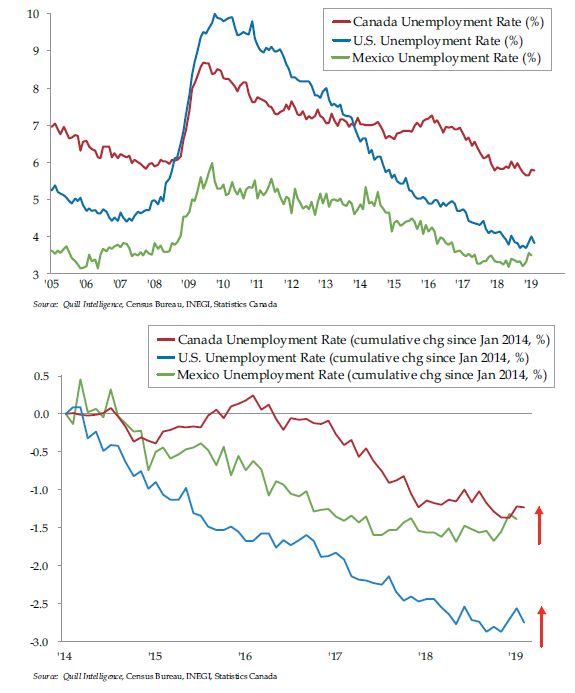

The harshest test for any economy is rising unemployment. A longer span comparison reveals similar movement and timing but vastly different scales. The depth of the damage that followed the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble should scare the daylights out of the Bank of Canada perched atop an even bigger housing bubble and the debt that inflated it with the added twist of a deep reliance on its petroleum and lumber exporting industries. At the risk of connecting one too many dots, Canada’s next recession could be one for the postwar history books.

Gauged by joblessness, the last recession in Mexico was relatively tame compared to that of its northern neighbors. The rush of skilled workers back into Mexico as the U.S. housing bubble de- flated leaving millions of illegal workers without work could have acted as an economic cushion of sorts, fluffed up further by record remittances of lifetime savings as the job market here dried up. Pay close attention to the data behind the headlines and you will appreciate that the numbers of illegal immigrants coming from Mexico in recent years has collapsed. The human traffic that so besets politicians is from further south, where the drug trade sadly dominates many Central American nations.

Zeroing in on the last five years illustrates both the rapidity of the decline in the U.S. unemploy- ment rate and how much less slack we had at the end of the cycle. While there is no such thing as a straight line in either direction, we’re confident we’ve seen the lows for all three countries.

NAFTA Unemployment Rates Trend and Turn Together

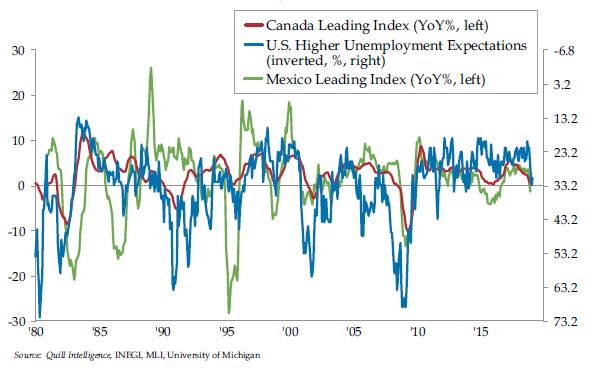

Our confidence in this call stems from our holy grail of economic indicators, expectations that unemployment will rise hitting its critical threshold recently. This has since been corroborated by a broadening breadth of sectors being featured in headlines reporting of layoffs in this or that industry, led as we’ve been writing, by cyclicals. The resilience of the stock market is that much more remarkable given the rising political will to attack the monopolies and Big Brother tech gi- ants that seem to have mutated in Silicon Valley. As one astute subscriber predicts, when investors finally wake to the existential threat to the mega-tech firms’ business models, the financials are sure to follow given the fortunes of the former have so benefitted the latter.

In the meantime, we would note that along with the breaching of our holy grail, both Canada’s and Mexico’s leading indicators are warning contraction is around the bend. Again, what we’re witnessing is a footrace to the bottom. It would be nice to single out one country as more resilient than the other, but domestic issues unique to each suggest we’ve no such luck to hang onto.

If it Leads, It Will Bleed

You may note Mexico’s leading indicators have slid into negative territory with the greatest speed. The ECRI’s Mexican Long Leading Index validates the conclusion that Mexico’s ongo- ing slowdown is set to deepen. Achuthan noted that, “Mexico is currently in a growth rate cycle slowdown that began last spring and, according to our data, there is no sign of an upturn, despite President López Obrador’s confidence that the economy is in good shape.”

In a March 11th Bloomberg Opinion piece, Shannon O’Neil, a senior fellow for Latin America Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York warned that Mexico’s leftist President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, referred to as ‘AMLO’ is reverting to old-school, corrupt ways to concentrate his power seat. There are, however, a few key differences between then and now.

“AMLO’s calculated strategy isn’t a new Mexican playbook,” wrote O’Neil. “It harkens back to the PRI’s heyday, when the party maintained economic and political control of businesses, labor, the countryside and any semblance of civil society.”

Back then the PRI, the once-dominant political party, had billions of dollars on hand as oil flowed in abundance and loans from international banks stuffed their pockets care of petrodollars. With oil production about half its peak and revenues falling fast against a backdrop of rangebound crude prices, AMLO will have none of his strongarm predecessors’ riches to ease his rise to power. NAFTA arguably invigorated the flow of funds with U.S. foreign direct investment in Mexico rising from

$15 billion in 1993 to more than $100 billion by 2016. But there’s nothing like the uncertainty of a volatile leader with designs on a de facto dictatorship to turn the tide of fund flows, and fast.

As per O’Neil, “This may be his undoing. Cancelled contracts, ratings agency attacks, and an- nouncements of new unfunded programs and projects are eroding domestic and international investor trust, slowing if not freezing the tens of billions in investment dollars needed to grow the economy by funding infrastructure, factories and salaries.”

And then there is the drug war, a whole other sort of economic plague. Experts on Mexico’s econ- omy recognize that just like any other industry, the drug trade generates a multiplier effect: $40 billion in profits can finance all manner of security forces, arms and luxury goods ranging from scotch to clothing to cars to say nothing of bribes to keep the business running smoothly. After applying the multiplier to Mexico’s $1.1 trillion, you’re talking about an industry with a mate- rial impact on the economy.

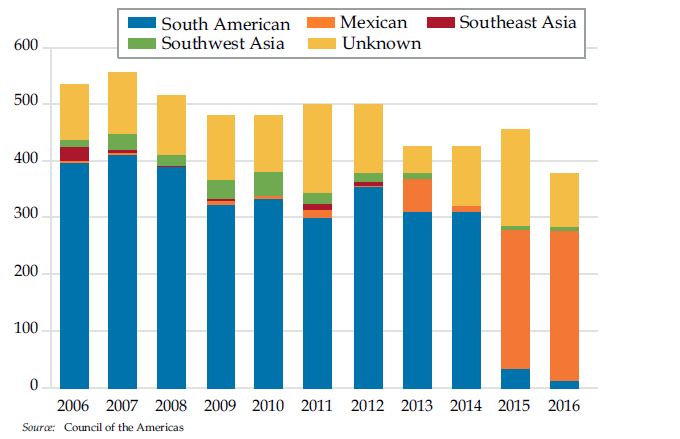

Of course, drug wars are not the stuff of chamber of commerce campaigns. Given the size of the drug trade in the United States – some $150 billion – it’s safe to say all manner of war will continue to be fought by rivals. In the decade through 2016, the heroin trade shifted from being dominated by South American producers to Mexico. And that means that many hotels along Mexico’s stun- ning shores will continue to have outsized vacancies. Many tourists won’t shed their fears that the drug war, financed as it is by wealthy kingpins, can’t spill onto the streets of once-coveted destinations at any moment as has been the case time and again.

The Power Shift from South America to Mexico

If anything, this next recession could be more damaging than those of a quieter, more peaceful past, one that also preceded the rise to dominance of U.S. shale producers. The so-called Shale Revolution has made us less reliant on our neighbors to the north and the envy of our woefully underinvested neighbors to the south. But that should not give the United States false bravado. All parties hesitant in one way or another about ratifying the new NAFTA would be best served appreciating that economic peace along our collective borders benefits the whole that much more than adversaries at the gates ever can or will.

The secret of the ’Ndrangheta’s success is omertà, an ideal El Chapo wishes would have shielded him from the 56 witnesses the prosecution called to testify against him. As for the symbiotic relationship between Canada, the United States and Mexico, it’s no secret that the success of any one applies exponentially to that of all of its neighbors. As is the case in Calabria, you can take in the cultures of all three countries without ever having to cross a border, which we should never forget is a blessing, not a curse.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.