China: What Are the Global Implications of the Changes in China’s Economy over the last Five Years?

January 4, 2022

GIC College of Central Bankers Chair, and GIC Vice Chair Peter A. Gold, Esquire, asked a selection of GIC Board Members and CCB Advisory Board Members for their outlooks on this question and China’s economy in general. We are pleased to share the analyses below for your review and sincerely invite your comments. We thank our contributors Michael Drury, Leland Miller, Kathleen Stephenson, J. Paul Horne and David Kotok.

Michael Drury, GIC Board Member, CCB Advisory Board Member, and Chief Economist for McVean Trading & Investments, LLC.

Another underappreciated political issue, is that the US may play the role of the globe’s central bank – controlling liquidity via dollar money supply – but because we run such a large trade deficit with China, we have effectively made them the global banker – deciding how that liquidity is disbursed. One of the lessons of the Great Financial Crisis is that after the Fed injected massive reserves into the US banking system, the government was not pleased at cautious banks failure to distribute loans as expected. As a result, during the COVID crisis, they simply dropped money directly on US consumers and businesses – bypassing the banks. A lot of that money ended up in China, as COVID exploded goods consumption globally and they are the world’s factory floor. We doubt that was the anticipated goal.

Meanwhile, as we like to follow the money, the question is where did these dollars go? Yes, China has been stockpiling a lot of commodities — at much higher prices, but not enough to absorb the full inflow, as they are still running a much bigger trade surplus. It did not flow into US treasuries, the deepest capital market in the world, as their holdings are still just $1 trillion. It is unlikely it passed through private Chinese citizens into US assets, as they have cracked down on that with stricter capital controls. Nor apparently are they lending gleefully to the developing world, as they were burnt by the Belt & Road Initiative – and so where their customers. Indeed, data suggests that investment dollars are flowing into China, exacerbating the trade deficit trend. As dollar liquidity has risen, so has the US equity market – far more than other global assets. One logical option is that China has been buying US equities. Charles Gave of GaveKal points out this is precisely what the Swiss central bank has been doing as there is not alternative. It is what Kuwait and Norway sovereign wealth funds have done to diversify risk as they contemplate a less energy dependent future.

What are the consequences of a booming Chinese trade surplus – at the same time they have a cooling domestic economy? They don’t need dollars to support domestic growth as they can simply print yuan. But they haven’t done as much as other nations. Even with loosening monetary policy, the yuan was the biggest winner in 2021. Both the current and past US Administration view Chinese economic growth as a strategic threat. Gary Gensler has been active in blocking Chinese firm’s direct access to US investment by stricter regulatory controls from the SEC. How will US politicians of all stripes view this potential development? The one issue that seems to cross the aisle in Congress is limiting China’s development. And what does it mean about the true strength of the Chinese economy if they have been significant beneficiaries of the US equity boom? Inquiring minds should want to know.

Leland Miller, GIC Board Member and Co-founder and CEO of China Beige Book

In 2020, the consensus view of China’s economic recovery proved severely overhyped, as we learned in 2021 when the initial industrial bounceback never gave way to a more balanced recovery in retail or services. Yet market consensus in ’21 was if anything too negative, as property worries surrounding the Evergande crisis never metastasized into broader contagion and a tightened credit environment depressed growth, but never collapsed it.

Heading into ’22, markets are once again of a singular view, with near universal expectations for a shift towards greater policy easing. That’s fair. The problem is, it tells us precious little about where the Chinese economy may be headed in 2022. China Beige Book data made clear that credit conditions in ’21 were remarkably tight—far and away the tightest we’ve seen in the decade-plus history of the CBB survey. With ’22 slated to be one of the most politically sensitive years in China this century, political (if not economic) considerations will require better conditions to boost sentiment.

That means, sure enough, we will see at least some mild level of policy easing. But the true question for investors is: will credit conditions merely be relaxing in 2022—a temporary release valve based on China’s political calendar—or will a turn back towards easing signify something bigger, suggesting a reversion back to the pre-2021 stimulus & juiced-growth playbook of the past decade?

So far, CBB data suggest that it’s the former—a temporary reprieve based on political considerations, not economic panic or back-tracking. But will this remain the case? We believe so, but it will be interesting to see if official rhetoric changes should job growth slow more precipitously than expected this year, or if Omicron (or another Covid variant) shuts down key parts of the economy for an extended period.

Kathleen Stephansen, GIC Chair Emeritus, CCB Advisory Board Member, Senior Economist for Haver Analytics, and Trustee of EQAT Trust Funds

China’s real GDP growth has slowed to a 4.9% rate in Q3:2021 from 7.9% and 18.3% in Q2 and Q1, respectively. Growth reached 6.5% in 2020 and is anticipated to reach 8.0% in 2021. Projections for 2022 are around 5.0-5.3%. Thanks to government stimulus, both domestic demand and net exports contributed strongly to growth last year. This is unlikely to last, as challenges arise. According to Morgan Stanley, China accounted for about 30% of pre-pandemic global growth. In 2021, China’s growth accounted for 25%. Part of this drop is reflecting the negative effects of the pandemic. Longer-run, the tension between two dynamics will likely put growth on a slower path: the aging of the population against the backdrop of the transformation of the economy away from the export-led growth model to a domestic-led one. This implies that China will no longer be engine of global growth.

J.Paul Horne, GIC Board Member, CCB Advisory Board Member, and Independent International Market Economist

While he (David) is right about financial market investors/observers having to abide by the policies set by (mostly) independent central banks, the unique role of the CCB is that our Fellows are free to comment on those factors influencing monetary policy and what policy changes they think could/should be made. And I think you’re right to consider China to be a growing influence on global monetary policies.

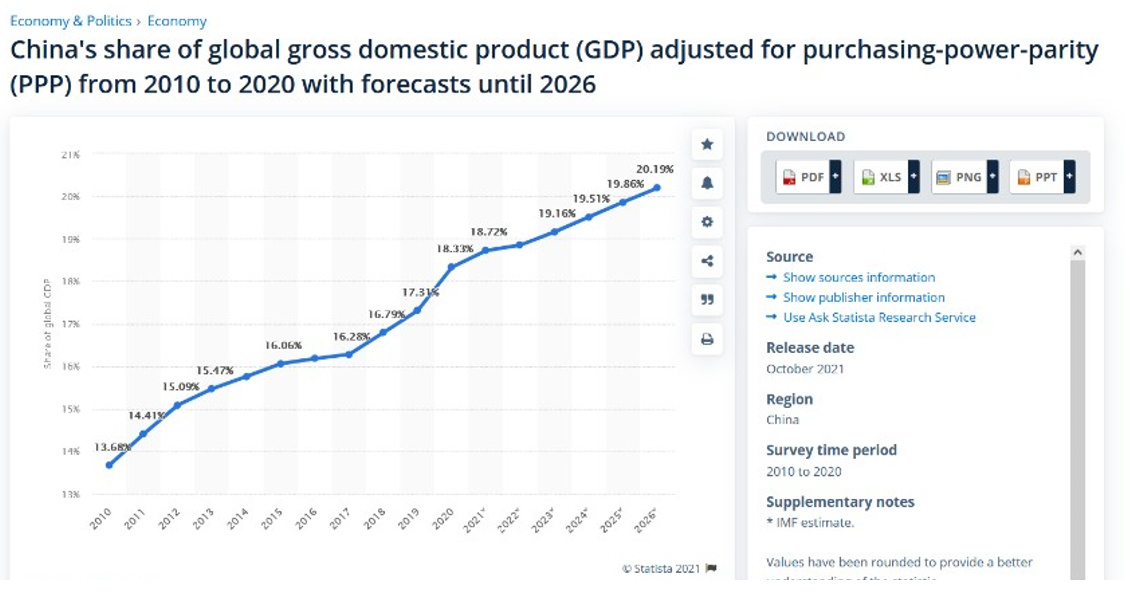

China’s weight in the global economy has grown dramatically and is expected to continue to over the next decades. China’s share of global GDP from 2010 to 2026, is projected by “Statista” to near parity with the U.S. If measured by Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), based on population, CH is already ahead of the U.S., according to the IMF.

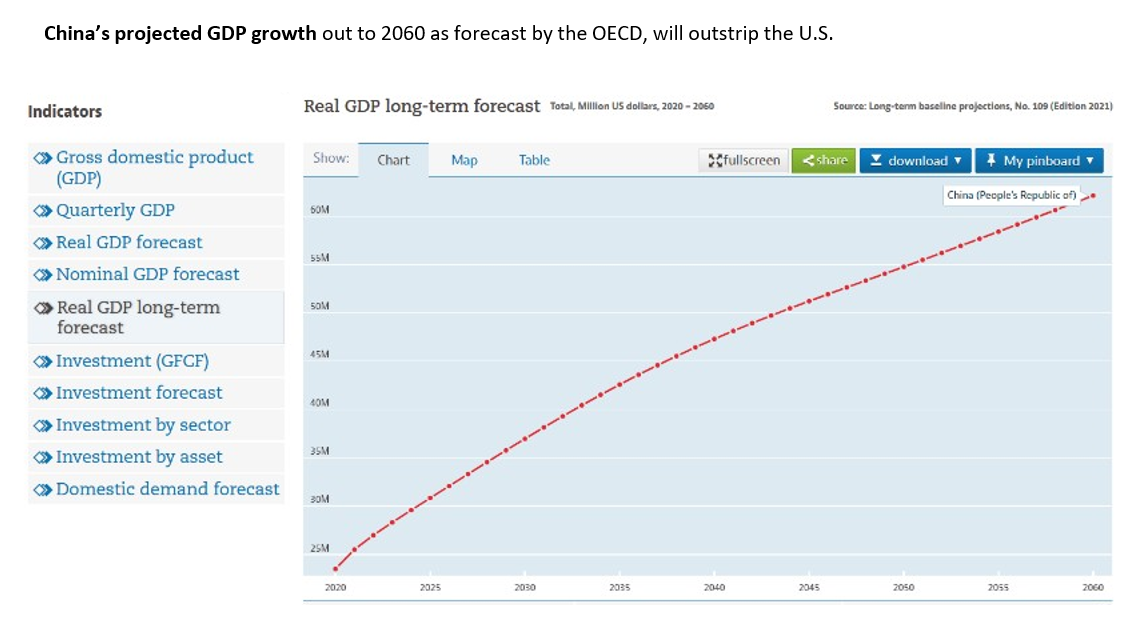

China’s projected GDP growth out to 2060 as forecast by the OECD, will outstrip the U.S.

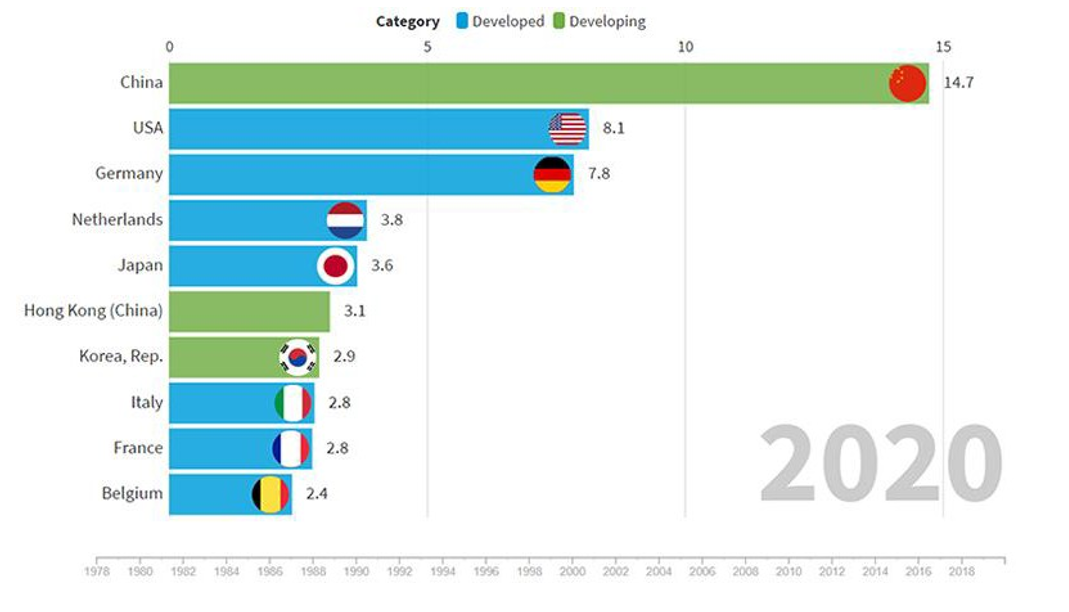

CH’s share of global trade already dominates, as the UNCTAD chart below shows, and may gain ground against the U.S. and Europe, as China gains competitiveness in high value-added goods & services.

The U.S.-China trade relationship is summed up by the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office:

+ U.S. goods and services trade with China totaled an estimated $615.2 bn in 2020 of which exports were $164.9 bn; and imports $450.4 bn, leaving a U.S. goods & services trade deficit of $285.5 bn.

+ China is the largest U.S. goods trading partner with $559.2 bn in total (two way) goods trade in 2020. Goods exports totaled $124.5 bn; goods imports totaled $434.7 bn with a U.S. goods trade deficit of $310.3 bn.

+ Two-way services trade with China totaled an estimated $56.0 bn in 2020. Services exports were $40.4 bn; services imports were $15.6 bn, producing a U.S. services surplus of $24.8 bn.

+ The Department of Commerce reports U.S. exports of goods and services to China supported an estimated 758,000 U.S. jobs in 2019 (latest data) of which 475,000 in goods exports and 283,000 in services exports.

FX. The USD’s dominant role in FX transactions of all sorts, as the world’s primary reserve currency, is unlikely to be threatened by the RMB any time soon, assuming the U.S. does not make a major policy mistake. Nor would the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) want the RMB to be a reserve currency since that would expose China policy-makers to daily market pressures they would prefer not to face. But as the recipient of hundreds of billions of USD annually on a net basis, China’s role in international capital movements and influence on U.S. and European interest rates will grow over time. The PBOC can, however, manipulate the RMB’s value against the USD and EUR which has ranged RMB 6.3 to RMB 7.1 since 2018.

OMFIF cites two reports on the RMB’s internationalisation. The first was published in July by the International Monetary Institute in Beijing, and the second in August by the PBOC. The IMI points to its renminbi internationalisation index which measures trade in goods & services, as well as financial transactions. Total RMB transactions expanded rapidly in 2009-15, stagnated in 2016-19 and resumed growing in 2020. Holdings of renminbi rose in the private sector and official foreign exchange reserves.

RMB payments for trade in goods and services were major contributors to the index. The share of Chinese exports and imports settled in renminbi has increased steadily to 20%, with the share of renminbi receipts and payments roughly balanced.

China problems. Xi’s crackdown on high-flyers in the private sector is likely to continue as a way to consolidate his political power – at least until the Chinese Communist Party’s organization feels threatened. His regime’s management of bad debt sectors such as property, basic industry and banks will be a test of Xi’s competence. Similarly, managing the slowdown of GDP growth to a 5%-to-6% average rate, or less, over the next years, and its consequences for employment, will be difficult. The PBOC will be expected to manage monetary policy to ease the transition.

Foreign policy. Beijing thinks, correctly in my view, that the Biden administration is weak and may lose control of Congress in 2022; and that the American public has near zero tolerance for a military conflict with China. Therefore, like Russia with Ukraine, China is ratcheting up pressure on Taiwan to force the

U.S. to make long-term policy concession on China’s relationship with Taiwan. I think a military conflict is very unlikely.

Bottom line. The U.S.-China relationship is crucial to both countries and must be managed very cautiously. Our China hawks play to the rightwing populist part of the electorate and deliberately ignore the economic and trade importance of China. I agree we need to be firm in the face of Chinese pushiness with Taiwan, the South China Sea and SE Asian neighbors. But this is where U.S. diplomacy and economic policy-making must be used effectively. Blustering will not work.

David Kotok, GIC Board Member, CCB Advisory Board Member, and Cofounder and Chief Investment Officer, Cumberland Advisors

I’ve thought about the task that you invited me to participate in. So please let me stray from the original discussion which you broadly framed as China and central banking views and your desire to promote a conversation in the College (CCB).

The central bankers that we know personally and socially tend to focus on the interest rates of sovereign debt denominated in their respective currencies. That makes sense since that is how they apply their policy-making decisions. They also look at financial stability to see if markets are functioning. That is also part of their responsibilities.

At Cumberland Advisors, we are not policy-makers. As an independent investment advisor we have to deal with the policies given to us by the central bankers. We may support them or we may criticize them but, in either case, we have to accept them. Our job is to look at our forecasts (not theirs, although we examine theirs) and to derive our own independent analysis of the impacts of policies and what that means for our clients, both individual and institutional.

One of the things we look at daily is credit spreads of all types. That is where the highest frequency (daily) changes in financial stability can occur. You asked about China but I am going to share a view of both China and of Russia.

I consulted Fred Feldkamp (a name known to some). He is a long time and skilled observer of credit spreads. His publications on this subject are easily found. Fred has been a guest at Camp Kotok. He and others are part of a small global circle of friends who exchange views almost daily. I am fortunate to be among that circle.

Here is how Fred characterized the summary of his credit spread index. Note that he has decades of history working with this dataset and deriving estimates from it. I may add that the findings he offers are disturbing. They suggest trouble ahead for western governments like the United States.

Fred wrote to me in commenting about the series I have published on the statistical discrepancy between GDP and GDI. I will excerpt and quote the email having obtained his permission to share this commentary with others including the CCB.

Excerpt #1.

“On Thu, Dec 23, 2021 at 11:08 AM Frederick L. Feldkamp wrote: The discussion is wonderful, David. I reiterate, however, that the “discrepancy” noted is primarily the consequence of the extremely low credit spreads since Biden was elected over Trump. The spread index was 530 bps higher then, than now, an annualized profit advantage of more than $2.65 trillion per annum gained by taking money from intermediaries and giving it to the productive sector. It is the ultimate conclusion to what Adam Smith published in 1776 which supports the comparative advantage of a free enterprise democratic republic.”

Excerpt #2.

“On Dec 23, 2021, at 7:57 AM, Frederick L. Feldkamp wrote: Putin has no choice. By controlling credit to extract his “cut”, to the extent markets for growth firms exist, spreads are over 10% above Russian gov bonds, or something like 18% per annum. US HY bonds are at 4.49% today (over 9% at the March 2020 peak) or 14% per annum below Russia. My index has total spreads below 1000 bps today (lower than the lowest under Trump) and 3,800 less than in Russia. He needs war to survive.”

Excerpt #3.

“By my count, the US spread index I use fell another 12 bps yesterday (112 bps below the Dec. high, on 12/3). That implies a $560 B per annum increase in US potential growth. NOT BAD for 18 days at the end of a VERY good year. On Thu, Dec 23, 2021 at 9:12 AM Frederick L. Feldkamp wrote: BTW, about the same differential in growth spreads exists today in China. That is a gigantic barrier to growth–it limits choices to those favored by the “ruler” just as Europe’s kings produced before democracies blossomed. In the end, David, that is the reason a “republic, if we can keep it” is vital to progress. I once explained that to a gov. group in Beijing (they only asked the question in an old limo that they knew was not bugged).”

Peter, this is a little different than we discussed but it may serve as a trigger for some serious conversation among the GIC leadership, CCB fellows and the Advisory Board.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.