Living with Risk: The COVID-19 Iceberg

September 1, 2020

“The pandemic crisis now rests on a fulcrum. On one side is Covid-19 and every possible action that might prevent people from contracting and dying from infection.

“On the other side is everything else that matters: livelihoods that allow people to feed and shelter their families; civil liberties; the education of children; social well-being, including the prevention of loneliness, isolation and domestic violence; and all other medical conditions, from cancer and heart disease to dental emergencies.” – Joseph Ladapo, MD, The Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2020

Sooner or later, the threat of the novel coronavirus epidemic will fade. The virus will not be eradicated, but we will adapt and learn how to live with the risk of SARS‑nCoV-2 infection. (The virus will also adapt, something very much on the minds of researchers and public health officials.) Our parents, grandparents, and their ancestors lived with the risk of polio, smallpox, plague, cholera, typhus, and a host of viruses and bacterial infections in the epic battles between man and infectious disease. They didn’t live happily with these risks, but humanity survived. In fact, it has thrived, the evidence being that today the world population is the largest it has ever been. It is also the healthiest and wealthiest it has ever been, which gives a clue as to who is winning the never-ending war between viruses and human beings.

Most of the people in the world live with viral risk on a daily basis and always have. “I’ve always lived with [the possibility of] dengue fever,” recalls Victor Canto, a respected economist, prolific author, and investment manager who is in the same discussion group that includes both of us and Drew Senyei, the doctor whom one of us (Siegel) interviewed in the April 2 Enterprising Investor column. Dengue fever is also called breakbone fever, not because it breaks your bones but because it feels that way. You don’t want it, but in Canto’s native Dominican Republic, an upper middle-income country, it is endemic and you are exposed to that risk whether you like it or not.

Life is risk. We adapt, innovate, and make intelligent tradeoffs to go forward. We manage risk, because we cannot live risk-free, even if we wanted to. In fact, to change is to take risks, and all economic progress comes from change.

The old normal

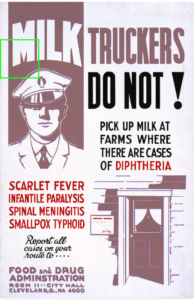

If you have any historical perspective at all, you know that the Old Normal with which people lived for almost the entirety of human existence resembled Canto’s Dominican Republic, except that it was much worse. Exhibit 1 shows a 1937 public health poster from that archetypical First World country, the United States.[1] Milk truckers (the people who picked up milk from farmers) were exhorted not only to avoid people who were suffering from diphtheria, smallpox, and a long list of other diseases but to report them. This was a sensible policy; as the celebrated investor and armchair philosopher Cliff Asness recently wrote, there are no libertarians in pandemics.[2] But the sad part is that it was also a necessary policy, not that long ago.

We’ve made so much progress against viruses and bacteria that the 1937 poster feels like a dispatch from another planet. Not long before that, in 1924, a bacterial infection took the life of U.S. President Calvin Coolidge’s young son, Calvin, Jr. But only a few years later, human ingenuity and innovation brought us “sulfa drugs,” antibiotics, and changed our lives for the better forever. And, on March 14, 1942, a young woman in Connecticut named Anne Miller was the first American was treated with penicillin, a new broad-spectrum antibiotic much more effective than sulfanomide. She recovered quickly after facing near-certain death from septicemia when all other treatments had failed. She lived to the age of 90. Now we transplant organs regularly, reattach retinas painlessly by shining a laser beam into the eye, and (on an experimental basis) repair defective human DNA using a technology called CRISPR. We are accustomed to medical miracles. But we should not take them for granted. The war between viruses and human beings is still raging, and probably always will.

We have made strides in our battles against bacteria. They are still evolving, but we are winning. In our battle with viruses, however, they still have the upper hand. New viruses keep arriving. While we wait for the virus to become low-level endemic, as its predecessors did, we can only hunt for vaccines and treatments to blunt the spread and lethality of the virus. Novel coronaviruses – SARS, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2 – are particularly nasty. We have no neutralizing antibodies, and the virus knows no borders and rapidly burns through the population.

So we should not be entirely shocked that we have reverted to using technologies from the 1918–1919 influenza epidemic, namely masks and social distancing, to fight a 21st-century coronavirus and the associated COVID-19 disease. But, as Dr. Ladapo said in the epigraph, the costs of using only these technologies and no others are extraordinary: “everything else that matters.” We did not evolve to live in social isolation and idleness, and we are neither productive nor happy in that condition. Eventually many of us will suffer and/or die from these second-order effects as human progress stalls and then falls into reverse, unless we act vigorously to counteract the second-order effects.

The new normal: Lockdown economics

What is new this time is that public authorities in much of the world, including the governors of forty-five of the fifty U.S. states, have issued emergency orders that have locked down large swaths of economic and social activity – schools, restaurants, church services, weddings, and funerals, as well as most of the factories and offices that produce the world’s goods. Internal and external travel restrictions have compounded the economic paralysis.

These lockdowns, while apparently beneficial if imposed early and briefly, have delivered an enormous economic shock – one so large it is a “crisis” by any historical measure. In the U.S., the decline in GDP in just three months has wiped out five years of economic growth, and on a per capita basis the standard of living may have fallen to 2004 levels. Government employment is down 1.5 million jobs and is at year-2000 levels. Not even in the Great Depression was any one quarter’s economic decline so rapid. Worse, the economic freefalls have been devastatingly uneven. Some industries, such as air travel and hotels, have been almost obliterated, while online shopping and delivery jobs boom.Many core commonwealth goods provided by governments are at risk. Many needed medical procedures are postponed. Government revenues have collapsed while debt levels rapidly expand.

The economic prognosis: Great depression 2.0, or a rapid plunge followed by a quick recovery?

We do not expect Great Depression 2.0 because, unlike the first Great Depression, this one was imposed by political authorities as an attempt to control the spread of a virus. What can be imposed from above can be relieved from above.

When the virus is controlled and the restrictions are lifted, pent-up supply and pent-up demand will collide. The boom could be tremendous as workers rush to reclaim jobs and begin to spend confidently, and as capital (of which there is no shortage) is deployed in recapitalizing damaged businesses, many of which will be under new ownership. The trick is in achieving a balance between two goals: the need to control the virus so the boom we’ve just described is not stopped in its tracks, and the need to avoid any more capital destruction than is absolutely necessary.

If we knew exactly how to do this, we’d tell you. We don’t, but in earlier work we said that the effects of an economic shutdown are nonlinear. A two-week shutdown is like a long, boring vacation. A two-month shutdown is a monumental pain in the neck, but one can recover from it: the Germans earn as much in a year as Americans do in ten months, and Germany is quite a nice place.

But longer than that and basic infrastructural goods and services begin to fall apart quickly. Human capital decays (people forget how to do things), and our children’s intellectual growth stagnates as they miss more and more school. We are approaching five months with only moderate liberalization of economic activity. And, after two years, we are likely to be headed back to the Dark Ages. We don’t know if the trip back to the Dark Ages sends us to 1993, 1933, or 1333. But, whatever the destination, we cannot allow that trip to begin.

We do think that some changes in behavior will occur, but they are unlikely to permanently change our basic nature, which is to seek out human connection and to try to make progress. People adapt well to new normals when they bring us connectedness and progress: it’s no mystery why today’s internet, mobile phone, and social media companies have been the fastest-growing global companies the world has ever seen. Apple is the largest company by market cap in the world, almost equal in value to the whole Russell 2000 (!). Amazon is everywhere. Facebook has 2.6 billion users – one out of every three men, women, and children on the planet. Zoom went from an unknown company to a global giant in less than a year.

Better yet, the word zoom has gone from a company name to a verb (“I’ll zoom you in the morning”) in a few months. It took years for Xerox and Kleenex to become generic words for the products they represent, but today’s world moves faster.

People will strive to return to their old normal lives in a hurry, and they will pull along the parts of the new normals that they like. The value of the gains from social interaction – for business, education, family life, fun, and spiritual renewal – is just too high for people to abandon in search of an illusory bubble of safety. Just as the social distancing of the 1918–1919 flu pandemic pretty quickly gave way to innovations like widespread electrification and work-saving appliances in the roaring 1920s, and the little-remembered but very serious flu pandemic of 1957 yielded to the groovy 1960s,[3] the medium-term future will look a lot more like “business as usual,” enhanced by innovations, than it will look like the dreary present.

The utilitarian calculus

During acute crises, from wars to natural disasters like famine, earthquakes, and storms, the collective power of government rises to provide a response: directing the economy in a wartime production mode; mobilizing water, food, and shelter after hurricanes; and even pursuing narrow one-time projects like going to the moon, walking on it, and then coming back (with rock samples). But dealing with regularly occurring novel viruses, which are dispersed and unpredictable, requires a different approach to decision-making.

The only way the conflicting COVID-19 needs, dangers, and short- and long-term goals can possibly be balanced is by thinking of them as an optimization problem – the act of balancing decisions with the aim of achieving the highest utility when summed across all citizens. This balancing act goes back to Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarian calculus, an Enlightenment-era attempt to put numbers to happiness and tragedy that has annoyed those who do not understand it ever since.[4]

The utilitarian calculus basically says that any action should maximize the summed utility of all the people in the world, taking into account positive and negative aspects of utility (death is very negative but it is possible to imagine a fate worse than death), and including the effects that you can see and those you cannot.[5] Utilitarian-calculus problems are familiar to philosophy and ethics students who have been asked questions like how many trolley passengers they would sacrifice to save a pedestrian.

This way of viewing ethical problems is not the right way but the only way to frame the COVID-19 dilemma. To those who object to utilitarianism on the ground that there are moral absolutes, we’d note that extreme examples and polar cases are revealing. This is completely unrealistic, but here goes: would you be willing reduce the world’s economic output to exactly zero (meaning that nobody eats, starting right now) to save one life? Of course not. So there is a number, an unacceptable level of cost, beyond which the saving of one life requires too much sacrifice from everyone else.

At the other pole, would you pay one dollar to save that life? Of course, you would. Between those two extremes of cost, there is an equilibrium. That equilibrium, wherever it lies, is the utilitarian solution to the problem. Of course, we don’t know what that solution is, but we know there is one. One can begin by framing the problem in the right terms.

This “utilitarian calculus” may seem cold, but it is at the heart of humanism, the philosophy to which we subscribe (and upon which Western civilization is based, along with Judeo-Christianity and some nod to Greco-Roman classicism). It is part of the political economy of how we organize to provide commonwealth goods and maintain our personal and economic freedoms. Without it, how else can we make pandemic-related decisions that involve trading years of life now against years of life in the future? Any other framing necessarily leads to a narrow, suboptimal solution that will favor one person or group over another for no morally acceptable reason, or worse, yields to full external control of everyday life.

A riskless society is “unattainable and infinitely expensive”

To return to where we started, life cannot be free of risk. We face a risk that didn’t exist when Exhibit 1 was created: nuclear war. We also face climate risk, which existed, but we didn’t know that it did. We were ignorant of climate risk only because we have short memories: the Little Ice Age, which lasted from the 1300s until the 1800s, caused a series of famines that drove Europeans to explore and settle in the Americas in search of new land, leading to the almost total destruction of the native population. Some millennia earlier, Doggerland, a shelf of well-populated land between what are now England and Germany, sank beneath the sea because of warming and the consequent sea-level rise. Now that’s risk!

A riskless society is “unattainable and infinitely expensive,” said the physicist Edwin Goldwasser. This phrase is the title of the contribution by one of us (Siegel) to the CFA Institute Research Foundation’s book of readings analyzing the great crash of 2007-2009.[6] The impossibility of eliminating all risk is even more germane to the current situation than to a financial crash. We could isolate every individual from every other, work nonstop on a vaccine (but who would do the teamwork?), and only permit social functioning to resume when the vaccine is found and widely distributed, but by then we would have impoverished ourselves all the way back to the standard of living found in Doggerland before it sank. A few axes and shards of pottery remain, telling us much about how life was lived then. We cannot allow that to happen to us, so we had better take the steps needed to assure that we won’t.

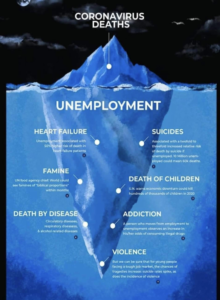

The COVID iceberg

The great 19th century French economist Frédéric Bastiat famously distinguished “what can be seen” from “what cannot be seen.” Policymakers focus almost entirely on the former while neglecting the effects on the latter. This observation is relevant to the COVID-19 pandemic.

What formerly could not be seen is rapidly being seen, as Exhibit 2 illustrates: disruptions to the global food supply chain, medical and psychological effects that include stress-related heart disease, untreated complications of diabetes and cancers, suicides, homicides as violence spirals upward, and the slow death (aided by drugs and alcohol) that accompanies the sudden poverty of the wallet and of the spirit.

Another major loss is from delayed or avoided medical diagnoses and treatments, due to unavailability of doctors and/or fear of infection from going to the hospital. Cancer treatments are being skipped. Diagnoses of heart attacks are way down, not because coronaviruses are good for your heart, but because marginal symptoms are being ignored instead of investigated.

Bill Gates has pointed out yet another casualty: “we will have lost many years in malaria and polio and HIV [remediation] and the indebtedness of countries of all sizes and [degrees of] instability. It’ll take you years beyond that before you’d even get back to where you were at the start of 2020.”[7] And Gates calls himself an optimist!

In the long run, by which we mean the decade or two after the SARS-nCoV epidemic has been brought under control (for it probably will not be eliminated), we are more concerned about deaths from these related causes than about the immediate toll of the COVID-19 disease. It is likely they will outnumber deaths from the virus itself.

This recitation of losses is not intended to suggest that we should just “let it rip” and allow the pandemic to take its course out of concern for the economy and the well-being of those who do not catch the disease. That would be insane. We enumerate these costs so that the global optimization problem is framed correctly, that’s all.

Source: Dan Mitchell

Note: “Death by disease” should also include death due to delayed medical diagnosis and treatment. Coronavirus deaths during the pandemic period must be compared with deaths from economic causes and delayed or forgone medical treatments over the next five to ten years, not just over the same period as the pandemic.

Last word

As we adapt to the SARS-CoV-2 virus – for that is what our almost infinitely adaptable species is going to do – we expect to be on the other side of Dr. Ladapo’s fulcrum where “everything else that matters” is renewed. What matters includes livelihoods that allow people to feed and shelter their families; civil liberties; the education of children; economic and technological growth; social well-being, including the prevention of loneliness, isolation, and domestic violence; and the treatment of all other medical conditions, from cancer and heart disease to toothaches.

The sooner, the better.

Click here to view the original post through the CFA Institute or visit www.larrysiegel.org.

[1] Interestingly, the Dominican Republic has a higher PPP GDP per capita today than the United States did in 1937, adjusted for inflation. (PPP = purchasing power parity.)

[2] https://www.niskanencenter.org/libertarians-need-government-in-finance-as-in-public-health/. I am paraphrasing Asness’ comment. Asness noted both the health and economic aspects to the emergency, adding that “economic dangers do become health dangers to the vulnerable” (tweet from @CliffordAsness at 6:36 PM on March 15, 2020). To that I would add that we all become the vulnerable if the economic damage is sufficiently large.

[3] A short, sharp depression followed the 1918–1919 pandemic and a deep but brief recession followed the 1957 pandemic. So the 1920s did not roar and the 1960s did not groove immediately.

[4] The utilitarian calculus is not an abstract problem in philosophy: when it comes to autonomous vehicles, you have to code the rules in algorithms. There is already a surprisingly large literature on this topic. See Bergmann, Lasse T., et al., 2018, “Autonomous Vehicles Require Socio-Political Acceptance—An Empirical and Philosophical Perspective on the Problem of Moral Decision Making,” Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience (published online February 28), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5835928/.

[5] The solution must be physically, economically, and morally possible. We cannot (at present) enrich ourselves by mining asteroids, or save lives by traveling back in time and killing Hitler, or by declaring everyone economically equal without also considering the consequences to productivity.

[6] Siegel, Laurence B. 2009. “A Riskless Society Is ‘Unattainable and Infinitely Expensive’.” In Laurence B. Siegel, ed., Insights into the Global Financial Crisis, Charlottesville, VA: CFA Institute Research Foundation, https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/research/foundation/2009/a-riskless-society-is-unattainable. For the full Insights into the Global Financial Crisis book, see https://www.cfainstitute.org/en/research/foundation/2009/insights-into-the-global-financial-crisis-full-book.

[7] Levy, Steven. 2020. “Bill Gates on Covid: Most US Tests Are ‘Completely Garbage’.” Wired (August 7), https://www.wired.com/story/bill-gates-on-covid-most-us-tests-are-completely-garbage/

Stephen Sexauer is SDCERA’s Chief Investment Officer and oversees SDCERA’s $12 billion Trust Fund, investment team, and investment consultants. In addition to the day-to-day operation of SDCERA’s Investment Division, he also assists SDCERA’s Board with determining the Fund’s investment policies, strategy and asset allocation.

Stephen Sexauer is SDCERA’s Chief Investment Officer and oversees SDCERA’s $12 billion Trust Fund, investment team, and investment consultants. In addition to the day-to-day operation of SDCERA’s Investment Division, he also assists SDCERA’s Board with determining the Fund’s investment policies, strategy and asset allocation.

Prior to joining SDCERA in 2015, Sexauer worked at Allianz Global Investors as Chief Investment Officer, US Multi Asset, of Allianz Global Investors Solutions, managing over $7 billion in multi-asset institutional portfolios and retirement income solutions. He is also the co-author of papers on retirement portfolios published in The Financial Analysts Journal, The Institutional Investor Journal of Retirement, and The Retirement Management Journal.

Sexauer graduated from the University of Illinois with a BS in Economics and from the University of Chicago with an MBA in Economics and Finance.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.